Remember when every sports apparel brand needed an app to be cool? Ten years ago, the Nike+Apple partnership was in its ascendency, while Under Armour and Adidas were splurging millions acquiring fitness apps like MyFitnessPal and Runtastic.

Back then, brand owners hoped that by mining our workout data from these apps, they could target us with personalized offers. The big idea was that if you knew how often someone went running, you could tell when they needed new running shoes.

Today, things look very different. Nike removed workout tracking from its website. And Under Armour still can’t figure out how to unlock the potential of its apps. So what went wrong? What happened to the digital fitness revolution?

Whatever happened to the Nike+ app?

On a recent trip to the Nike Store, I noticed something weird. A little sticker inside all the shoes told me that if I was a member of NikePlus, I could use the Nike app to check if my size was in stock.

This humble sticker stopped me in my tracks. When did that happen? How did Nike+, one of the first and finest fitness apps, become nothing more than a way to buy shoes?

Once I got over the initial shock, I realized this change has been a long time in coming. And it’s not just Nike. It seems all sports apparel brands are deserting digital fitness.

Photo: Graham Bower/Cult of Mac

The “plus” in Nike+ used to mean something

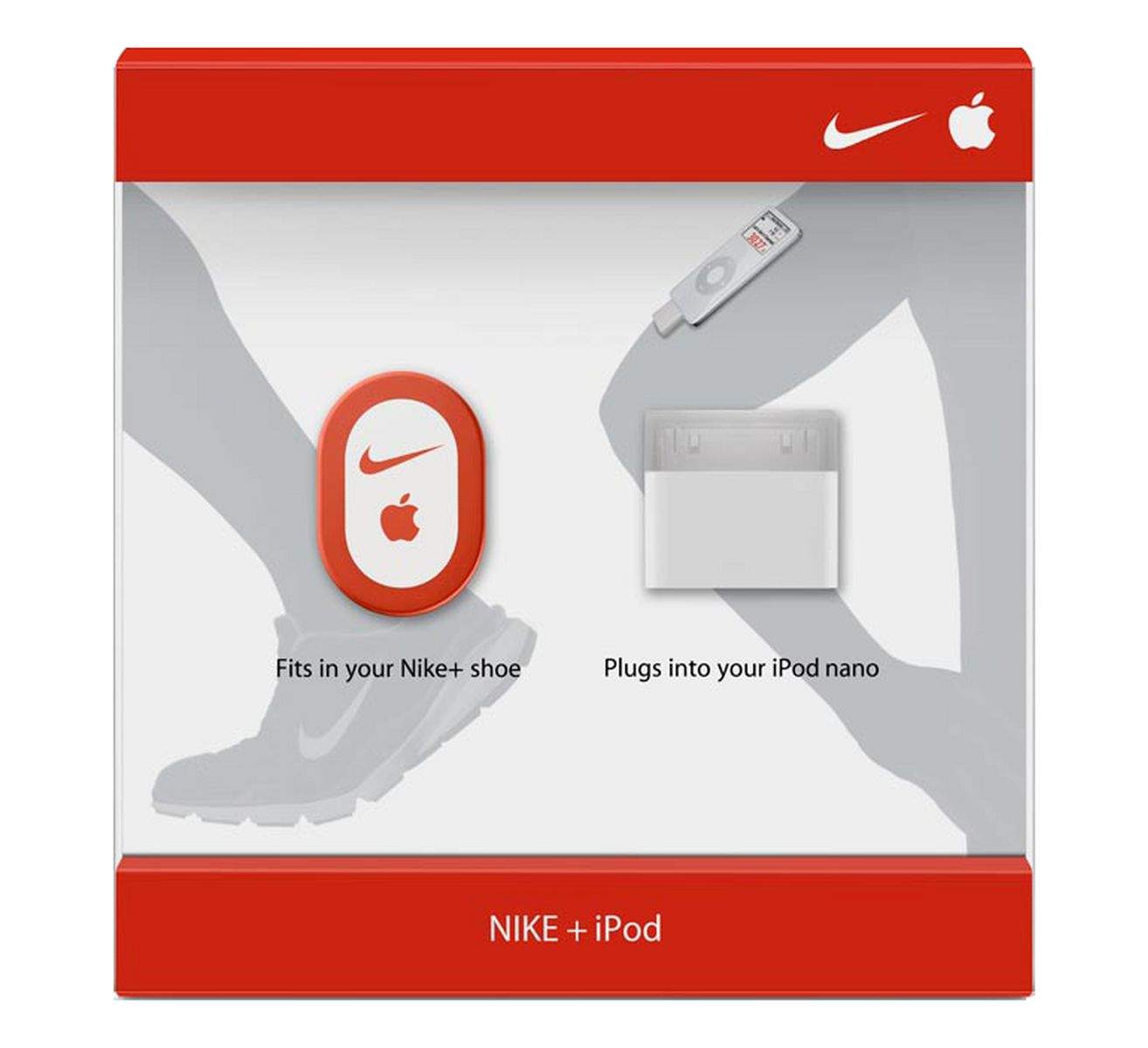

Way back in 2006 — long before the likes of Strava, MapMyRun, Runtastic and Runkeeper emerged — Nike+iPod sprinted onto the scene. The world’s first modern fitness app, it ran on iPod nano, communicating wirelessly with sensors embedded in Nike running shoes to track the pace and distance of your run.

Back then, the “plus” connected the Nike and iPod brands; hence Nike+iPod. But Nike’s ambition extended beyond a collaboration with Apple. In 2008, Nike introduced the SportBand, which could communicate directly with its shoe sensor, eliminating the need for an iPod.

Photo: Apple

Nike+ cut its ties with Apple

Thanks to SportBand, the “plus” in Nike+ no longer referred to a joint venture. Instead, Nike+ was now a fitness tech brand in its own right. A leader in the emerging quantified-self movement.

Nike didn’t abandon its partnership with Apple altogether. The iPhone 3G launched in 2008 with Nike+ built in. But Nike was no longer dependent on its friends in Cupertino.

More stand-alone Nike+ products soon followed: the Nike+ SportWatch GPS, the Nike+ GPS app for Android, and most notably, the FuelBand. With its graphical ring that tracked your daily activity, Nike+ FuelBand was the forerunner of today’s Apple Watch Activity app.

For a brief time, it seemed like Nike+ could do no wrong.

Photo: Graham Bower/Cult of Mac

Adidas, Under Armour and Asics look on with envious eyes

At its height, Nike’s digital division sported a team of 200 people working at its headquarters in Beaverton, Oregon. And its success did not go unnoticed by competitors. Adidas, Under Armour and Asics looked on with jealous eyes. Nike+ made them look like they were standing still, and investors were getting twitchy.

Back then, digital fitness tracking looked like the future of sports apparel. Brand owners invested big-time in electronic customer relationship management (aka eCRM). These systems gathered huge amounts of data about customers, enabling marketers to anticipate their needs and target them with the right offers at the right time.

Without data from fitness-tracking apps, brand owners risked missing out on this emerging eCRM opportunity. So they went on a shopping spree. Under Armour gobbled up MapMyRun, followed by MyFitnessPal and Endomondo. Meanwhile, Adidas nabbed Runtastic and Asics acquired Runkeeper. This left Strava as the only major indie fitness app standing.

The data mines are empty

Sadly, these fitness apps don’t seem to have delivered on the eCRM dream.

In an earnings call last February, Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank said of the company’s Connected Fitness unit, “We’re still figuring out how to unlock the true power of what [the] size and scale of this network means for us.” MyFitnessPal was acquired four years ago. If Under Armour is still figuring this out, maybe the anticipated synergies between fitness tracking and apparel sales are not so great after all.

Fortunately, Under Armour’s Connected Fitness unit has now started to turn a profit in its own right, through app subscriptions. That fact has not gone unnoticed by Nike, which recently introduced a premium subscription tier to its Nike Training Club app.

Switching to a subscription model in this way suggests that these apps are not paying their way through eCRM insights alone.

Is it all Apple’s fault?

So who’s to blame for bursting the fitness app bubble? One obvious culprit is Apple. The writing was on the wall for Nike’s digital division as soon as Cupertino started to show an interest in wearables.

Nike disbanded its hardware division in 2014, one year before Apple Watch launched. At the time, Cupertino’s plans for an “iWatch” were no secret. And with Apple CEO Tim Cook sitting on Nike’s board, it is perhaps no surprise that the folks in Beaverton decided to focus on software to run on Apple’s hardware instead.

But here’s the thing. Apple doesn’t just make the hardware and leave Nike to supply the apps. Apple products are famous for their tight integration of hardware and software. So when you buy a Nike+ Apple Watch, it comes with two running apps. One is beautifully integrated into Apple’s ecosystem. The other, Nike Run Club, looks like a superfluous bolt-on.

If you control the hardware, you control the software and user data

Apple likes to control every aspect of the user experience. The iOS Health app is designed to be the trusted custodian of all our health and fitness data. It makes perfect sense that Apple would prefer to use its own Workout app to gather this data, rather than relying on third parties.

Since Apple’s brand is not traditionally associated with sports and fitness, it helps to have the Nike swoosh in the corner of Apple Watch ads. It adds a sense of hip athleticism. But the Nike Run Club app no longer seems like a part of Cupertino’s master plan. It’s included as part of the deal, but if Nike decided to scrap it and focus on designing bands instead, I doubt they’d get any argument from Apple.

Similarly, while Garmin continues to support apps like Strava, it’s clearly the company’s objective to eliminate the need for third parties by providing everything everything you could possibly want on Garmin Connect.

As the market for fitness wearables matures and consolidates, stand-alone fitness apps are feeling the squeeze from hardware makers.

Time to focus on retail

The fact that brands like Under Armour and Adidas are still trying to figure out how fitness apps can help sell apparel suggests to me that the answer is they can’t. I suspect that a customer’s purchase history tells you far more about how often they buy sneakers than trying to analyze their workout data.

Maybe that’s why Nike transitioned Nike+ into a loyalty scheme called NikePlus and launched a shopping app (called simply “Nike”). The company that once led the sports apparel industry into embracing fitness apps is leading the way once again. But this time in the opposite direction.

![Why sports apparel brands are giving up on fitness apps [Opinion] Whatever happened to Nike+?](https://www.cultofmac.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/nrc2.jpg)